FEATURE

96

FIG. 8 (below):

Hotel des ventes, rue

Drouot.

Photo postcard.

Private collection.

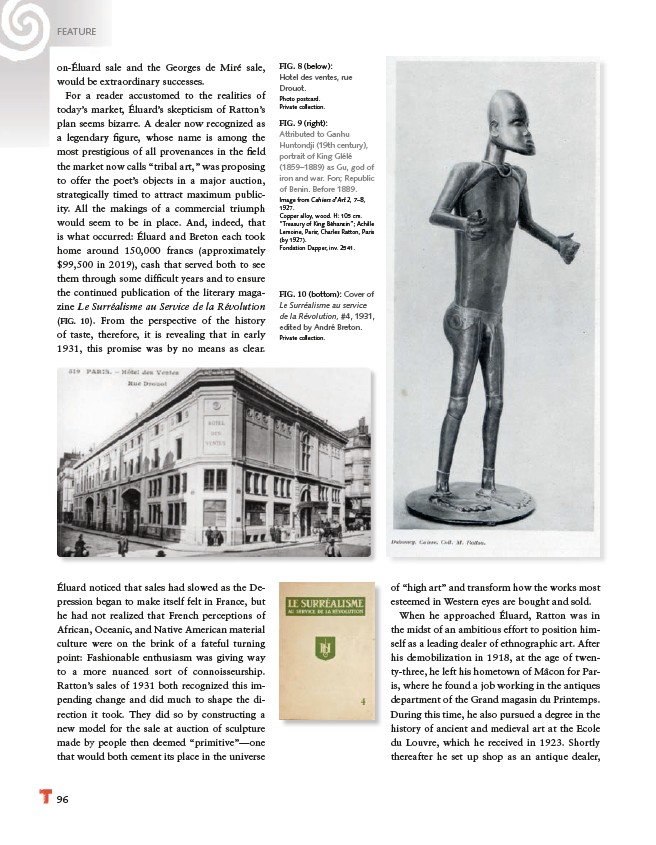

FIG. 9 (right):

Attributed to Ganhu

Huntondji (19th century),

portrait of King Glélé

(1859–1889) as Gu, god of

iron and war. Fon; Republic

of Benin. Before 1889.

Image from Cahiers d’Art 2, 7–8,

1927.

Copper alloy, wood. H: 105 cm.

“Treasury of King Béhanzin”; Achille

Lemoine, Paris; Charles Ratton, Paris

(by 1927).

Fondation Dapper, inv. 2541.

FIG. 10 (bottom): Cover of

Le Surréalisme au service

de la Révolution, #4, 1931,

edited by André Breton.

Private collection.

Éluard noticed that sales had slowed as the Depression

began to make itself felt in France, but

he had not realized that French perceptions of

African, Oceanic, and Native American material

culture were on the brink of a fateful turning

point: Fashionable enthusiasm was giving way

to a more nuanced sort of connoisseurship.

Ratton’s sales of 1931 both recognized this impending

change and did much to shape the direction

it took. They did so by constructing a

new model for the sale at auction of sculpture

made by people then deemed “primitive”—one

that would both cement its place in the universe

of “high art” and transform how the works most

esteemed in Western eyes are bought and sold.

When he approached Éluard, Ratton was in

the midst of an ambitious effort to position himself

as a leading dealer of ethnographic art. After

his demobilization in 1918, at the age of twenty

three, he left his hometown of Mâcon for Paris,

where he found a job working in the antiques

department of the Grand magasin du Printemps.

During this time, he also pursued a degree in the

history of ancient and medieval art at the Ecole

du Louvre, which he received in 1923. Shortly

thereafter he set up shop as an antique dealer,

on-Éluard sale and the Georges de Miré sale,

would be extraordinary successes.

For a reader accustomed to the realities of

today’s market, Éluard’s skepticism of Ratton’s

plan seems bizarre. A dealer now recognized as

a legendary fi gure, whose name is among the

most prestigious of all provenances in the fi eld

the market now calls “tribal art,” was proposing

to offer the poet’s objects in a major auction,

strategically timed to attract maximum publicity.

All the makings of a commercial triumph

would seem to be in place. And, indeed, that

is what occurred: Éluard and Breton each took

home around 150,000 francs (approximately

$99,500 in 2019), cash that served both to see

them through some diffi cult years and to ensure

the continued publication of the literary magazine

Le Surréalisme au Service de la Révolution

(FIG. 10). From the perspective of the history

of taste, therefore, it is revealing that in early

1931, this promise was by no means as clear.