107

quite a bit from him. He always had great

material that he enthusiastically showed me,

even though he knew I could not afford to

buy anything from him. At this point, I had

a lot of fake kifwebe masks that he identified

as such when he would visit my home. I was

very naïve. However, one time he said, “This

one is real, but why would you want it?” and

I felt I was getting somewhere. He showed

me how to see beyond authenticity, helping

me recognize the quality, beauty, menace, or

power of an object.

I should mention that looking back to when

I was a young artist trying to make sculpture,

I can now see that I copied work that I saw

in museums and galleries. I wasn’t making

anything original—in essence I was making

fake art. As I grew up and my work matured,

I saw myself in my work and I started to

make who I was. As I studied kifwebe

masks, this perspective of having made fake

art began to slowly help me recognize fake

masks. They were lifeless copies, without

passion, without a strength of purpose,

without a reason for being. I still made plenty

of mistakes, but this perspective, together

with a growing knowledge of the styles and

where they fit in time, wood age, carving

technique, etc., gave me greater insight,

inspiration, and confidence to acquire more

of these masks that spoke to me so strongly.

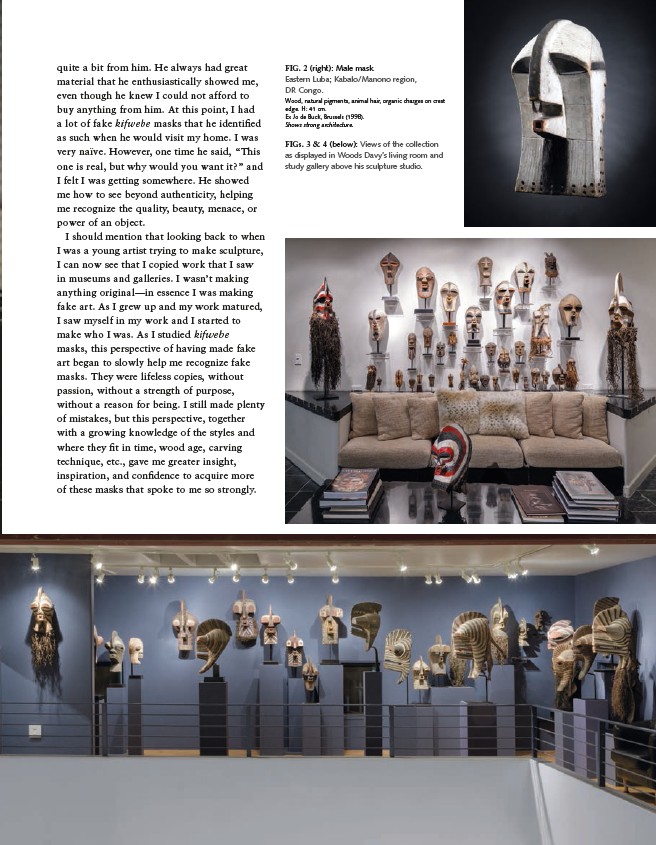

FIG. 2 (right): Male mask.

Eastern Luba; Kabalo/Manono region,

DR Congo.

Wood, natural pigments, animal hair, organic charges on crest

edge. H: 41 cm.

Ex Jo de Buck, Brussels (1998).

Shows strong architecture.

FIGs. 3 & 4 (below): Views of the collection

as displayed in Woods Davy’s living room and

study gallery above his sculpture studio.