83

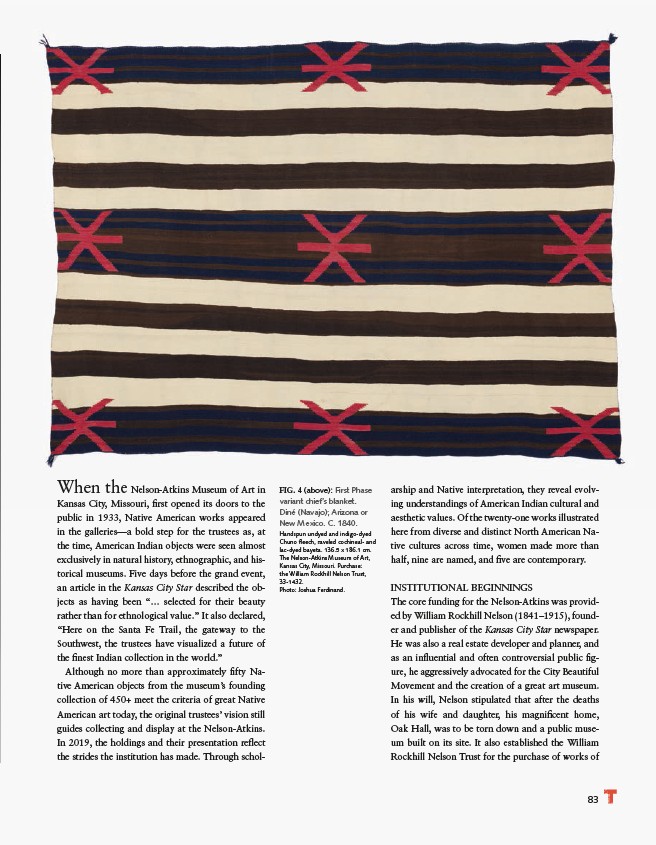

FIG. 4 (above): First Phase

variant chief’s blanket.

Diné (Navajo); Arizona or

New Mexico. C. 1840.

Handspun undyed and indigo-dyed

Chuno fleech, raveled cochineal- and

lac-dyed bayeta. 136.5 x 186.1 cm.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art,

Kansas City, Missouri. Purchase:

the William Rockhill Nelson Trust,

33-1432.

Photo: Joshua Ferdinand.

When the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in

Kansas City, Missouri, first opened its doors to the

public in 1933, Native American works appeared

in the galleries—a bold step for the trustees as, at

the time, American Indian objects were seen almost

exclusively in natural history, ethnographic, and historical

museums. Five days before the grand event,

an article in the Kansas City Star described the objects

as having been “… selected for their beauty

rather than for ethnological value.” It also declared,

“Here on the Santa Fe Trail, the gateway to the

Southwest, the trustees have visualized a future of

the finest Indian collection in the world.”

Although no more than approximately fifty Native

American objects from the museum’s founding

collection of 450+ meet the criteria of great Native

American art today, the original trustees’ vision still

guides collecting and display at the Nelson-Atkins.

In 2019, the holdings and their presentation reflect

the strides the institution has made. Through scholarship

and Native interpretation, they reveal evolving

understandings of American Indian cultural and

aesthetic values. Of the twenty-one works illustrated

here from diverse and distinct North American Native

cultures across time, women made more than

half, nine are named, and five are contemporary.

INSTITUTIONAL BEGINNINGS

The core funding for the Nelson-Atkins was provided

by William Rockhill Nelson (1841–1915), founder

and publisher of the Kansas City Star newspaper.

He was also a real estate developer and planner, and

as an influential and often controversial public figure,

he aggressively advocated for the City Beautiful

Movement and the creation of a great art museum.

In his will, Nelson stipulated that after the deaths

of his wife and daughter, his magnificent home,

Oak Hall, was to be torn down and a public museum

built on its site. It also established the William

Rockhill Nelson Trust for the purchase of works of