PARIS 1931

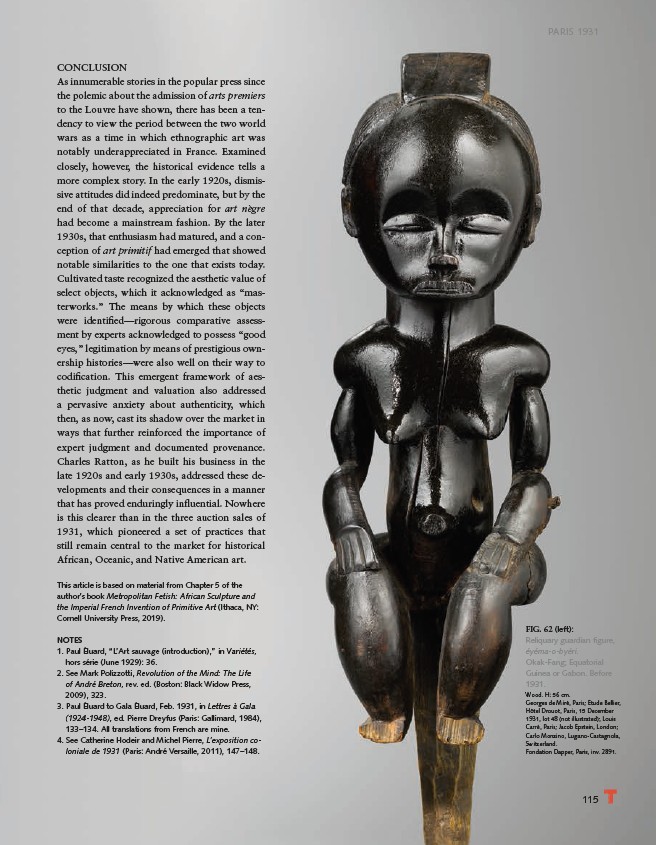

FIG. 62 (left):

Reliquary guardian figure,

éyéma-o-byéri.

Okak-Fang; Equatorial

Guinea or Gabon. Before

1931.

Wood. H: 56 cm.

Georges de Miré, Paris; Étude Bellier,

Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 15 December

1931, lot 48 (not illustrated); Louis

Carré, Paris; Jacob Epstein, London;

Carlo Monzino, Lugano-Castagnola,

Switzerland.

Fondation Dapper, Paris, inv. 2891.

115

CONCLUSION

As innumerable stories in the popular press since

the polemic about the admission of arts premiers

to the Louvre have shown, there has been a tendency

to view the period between the two world

wars as a time in which ethnographic art was

notably underappreciated in France. Examined

closely, however, the historical evidence tells a

more complex story. In the early 1920s, dismissive

attitudes did indeed predominate, but by the

end of that decade, appreciation for art nègre

had become a mainstream fashion. By the later

1930s, that enthusiasm had matured, and a conception

of art primitif had emerged that showed

notable similarities to the one that exists today.

Cultivated taste recognized the aesthetic value of

select objects, which it acknowledged as “masterworks.”

The means by which these objects

were identified—rigorous comparative assessment

by experts acknowledged to possess “good

eyes,” legitimation by means of prestigious ownership

histories—were also well on their way to

codification. This emergent framework of aesthetic

judgment and valuation also addressed

a pervasive anxiety about authenticity, which

then, as now, cast its shadow over the market in

ways that further reinforced the importance of

expert judgment and documented provenance.

Charles Ratton, as he built his business in the

late 1920s and early 1930s, addressed these developments

and their consequences in a manner

that has proved enduringly influential. Nowhere

is this clearer than in the three auction sales of

1931, which pioneered a set of practices that

still remain central to the market for historical

African, Oceanic, and Native American art.

This article is based on material from Chapter 5 of the

author’s book Metropolitan Fetish: African Sculpture and

the Imperial French Invention of Primitive Art (Ithaca, NY:

Cornell University Press, 2019).

NOTES

1. Paul Éluard, “L’Art sauvage (introduction),” in Variétés,

hors série (June 1929): 36.

2. See Mark Polizzotti, Revolution of the Mind: The Life

of André Breton, rev. ed. (Boston: Black Widow Press,

2009), 323.

3. Paul Éluard to Gala Éluard, Feb. 1931, in Lettres à Gala

(1924-1948), ed. Pierre Dreyfus (Paris: Gallimard, 1984),

133–134. All translations from French are mine.

4. See Catherine Hodeir and Michel Pierre, L’exposition coloniale

de 1931 (Paris: André Versaille, 2011), 147–148.