T. A. M.: This invitation to doubt is in many

ways an invitation to reconsider one’s intimate

relationship with African art. What have you

gotten from it personally?

K. G.: You understand that IncarNations is

more about raising questions than providing

answers. That being the case, I will not make

the mistake of offering some kind of defi nition

of what African art is for me. Let me simply

say that what makes it so powerful is that

when you look at an African work of art, it

looks right back at you—because it is alive and

imbued with a spirit.

81

K. G.: The exhibition tackles deep questions, but

my intention is not to give history lessons or to

preach morality to anyone. It does not pretend to

be encyclopedic nor representative of a continent,

and we avoid the too often repeated mistake

of claiming to speak for fi fty-four countries,

more than 2,000 living languages, and countless

identities and intertwined cultural histories.

My feelings as an African and my vision as an

artist have guided me in how I have designed

IncarNations. I essentially wanted to suggest

a change of orientation in the way that we

approach the question of history, how it is

recorded, and especially to what we call African

art. The Centre for Fine Arts that houses the

exhibition was designed and built by Victor

Horta between 1919 and 1928, and its grandeur

attests to the economic wealth that the colonial

era, which was at its apogee at the time, brought

with it.

The walls of the exhibition galleries were left

empty to help the visitor consider the context in

which they were erected. They are wallpapered,

and a few video installations and mirrors have

been placed on them. The wallpaper is made up

of the word BELIEVE, broken up into three lines

in such a way as to cause the word LIE to appear

in the viewer’s peripheral vision and to taunt his

eye, and that leads him to doubt what he sees.

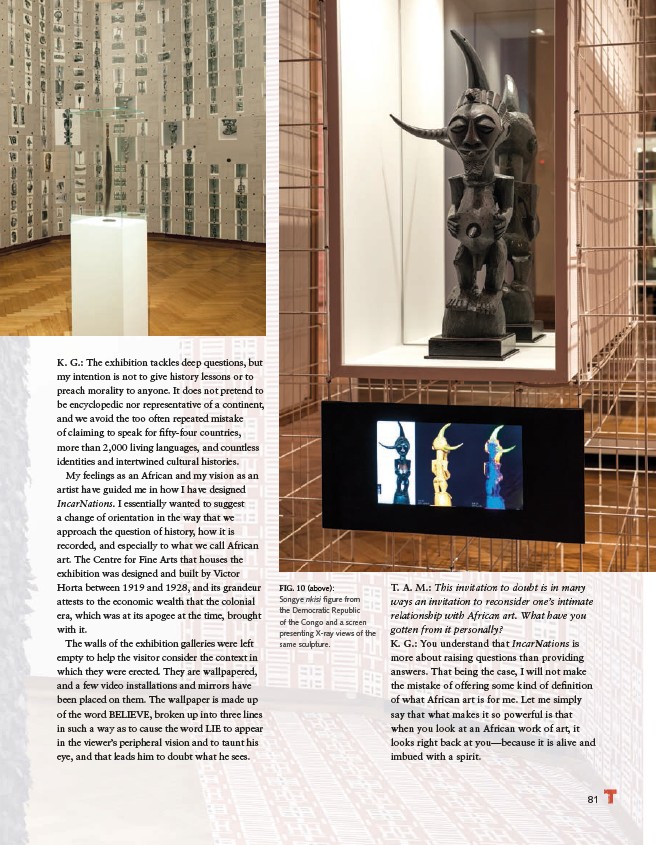

FIG. 10 (above):

Songye nkisi fi gure from

the Democratic Republic

of the Congo and a screen

presenting X-ray views of the

same sculpture.