95

pool their objects and split the proceeds of the

sale evenly.2

Ratton proposed holding the auction at the

Hôtel Drouot in Paris (FIG. 8) that coming summer.

1931

Éluard was pessimistic about the venture

and asked Gala’s advice. On the one hand, he

wrote, “A sale wouldn’t go too well at the moment,”

but on the other, “We must consider that

along with the few salable pieces we have, there’s

a far greater number that are unsellable on good

terms. And will the prices of the objects ever go

up again? It’s also a risk not to sell now.” For his

part, Ratton was confi dent enough in the venture’s

potential to give the poet an advance of

ten thousand francs. The dealer’s optimism derived

from the timing of the sale: “The colonial

exposition will be on then,” Éluard wrote, “and

he thinks it will help.”3 The enormous popularity

of the 1931 Exposition coloniale internationale

(FIG. 6), which promised visitors “a tour of

the world in a single day” and drew some eight

million of them to its elaborate pavilions in the

Bois de Vincennes, did indeed help.4 Ratton, in

collaboration with the slightly younger dealer

Louis Carré (FIG. 2), organized three highly publicized

auctions in 1931, of which two, the Bret-

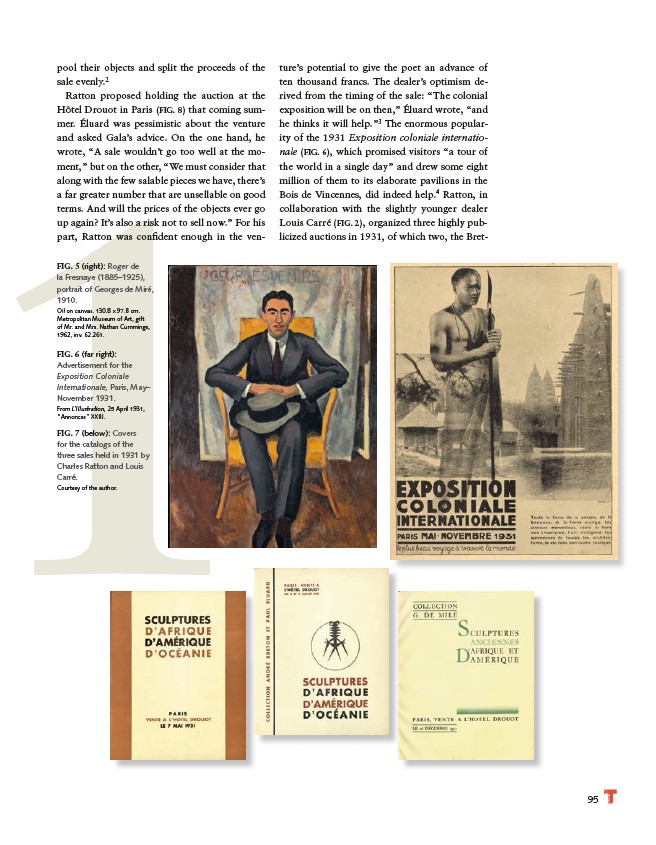

FIG. 5 (right): Roger de

la Fresnaye (1885–1925),

portrait of Georges de Miré,

1910.

Oil on canvas. 130.8 x 97.8 cm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift

of Mr. and Mrs. Nathan Cummings,

1962, inv. 62.261.

FIG. 6 (far right):

Advertisement for the

Exposition Coloniale

Internationale, Paris, May–

November 1931.

From L’Illustration, 25 April 1931,

“Annonces” XXIII.

FIG. 7 (below): Covers

for the catalogs of the

three sales held in 1931 by

Charles Ratton and Louis

Carré.

Courtesy of the author.