TRIBAL PEOPLE

126

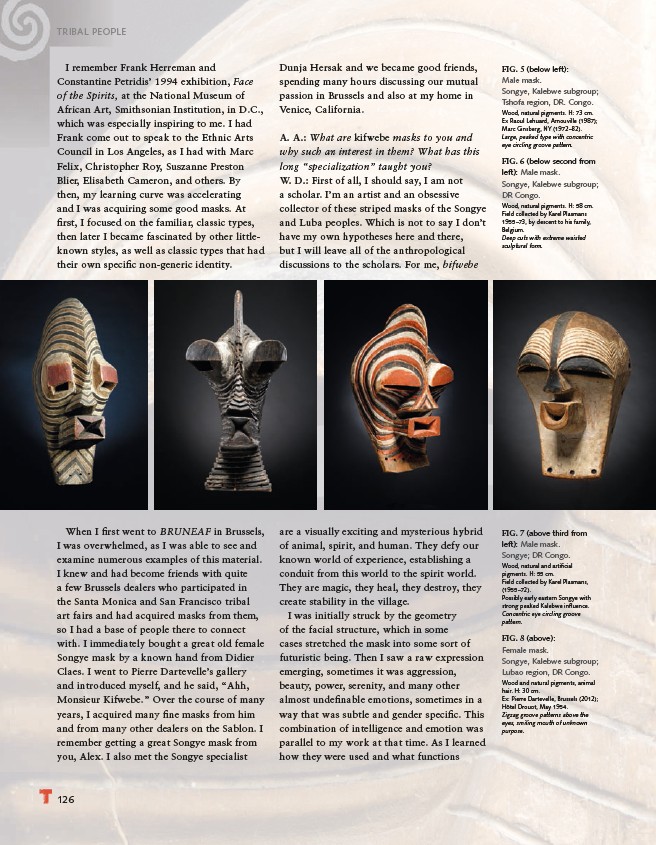

FIG. 5 (below left):

Male mask.

Songye, Kalebwe subgroup;

Tshofa region, DR. Congo.

Wood, natural pigments. H: 73 cm.

Ex Raoul Lehuard, Arnouville (1987);

Marc Ginsberg, NY (1972–82).

Large, peaked type with concentric

eye circling groove pattern.

FIG. 6 (below second from

left): Male mask.

Songye, Kalebwe subgroup;

DR Congo.

Wood, natural pigments. H: 58 cm.

Field collected by Karel Plasmans

1955–73, by descent to his family,

Belgium.

Deep cuts with extreme waisted

sculptural form.

FIG. 7 (above third from

left): Male mask.

Songye; DR Congo.

Wood, natural and artifi cial

pigments. H: 55 cm.

Field collected by Karel Plasmans,

(1955–72).

Possibly early eastern Songye with

strong peaked Kalebwe infl uence.

Concentric eye circling groove

pattern.

FIG. 8 (above):

Female mask.

Songye, Kalebwe subgroup;

Lubao region, DR Congo.

Wood and natural pigments, animal

hair. H: 30 cm.

Ex: Pierre Dartevelle, Brussels (2012);

Hôtel Drouot, May 1954.

Zigzag groove patterns above the

eyes, smiling mouth of unknown

purpose.

When I fi rst went to BRUNEAF in Brussels,

I was overwhelmed, as I was able to see and

examine numerous examples of this material.

I knew and had become friends with quite

a few Brussels dealers who participated in

the Santa Monica and San Francisco tribal

art fairs and had acquired masks from them,

so I had a base of people there to connect

with. I immediately bought a great old female

Songye mask by a known hand from Didier

Claes. I went to Pierre Dartevelle’s gallery

and introduced myself, and he said, “Ahh,

Monsieur Kifwebe.” Over the course of many

years, I acquired many fi ne masks from him

and from many other dealers on the Sablon. I

remember getting a great Songye mask from

you, Alex. I also met the Songye specialist

are a visually exciting and mysterious hybrid

of animal, spirit, and human. They defy our

known world of experience, establishing a

conduit from this world to the spirit world.

They are magic, they heal, they destroy, they

create stability in the village.

I was initially struck by the geometry

of the facial structure, which in some

cases stretched the mask into some sort of

futuristic being. Then I saw a raw expression

emerging, sometimes it was aggression,

beauty, power, serenity, and many other

almost undefi nable emotions, sometimes in a

way that was subtle and gender specifi c. This

combination of intelligence and emotion was

parallel to my work at that time. As I learned

how they were used and what functions

I remember Frank Herreman and

Constantine Petridis’ 1994 exhibition, Face

of the Spirits, at the National Museum of

African Art, Smithsonian Institution, in D.C.,

which was especially inspiring to me. I had

Frank come out to speak to the Ethnic Arts

Council in Los Angeles, as I had with Marc

Felix, Christopher Roy, Suszanne Preston

Blier, Elisabeth Cameron, and others. By

then, my learning curve was accelerating

and I was acquiring some good masks. At

fi rst, I focused on the familiar, classic types,

then later I became fascinated by other littleknown

styles, as well as classic types that had

their own specifi c non-generic identity.

Dunja Hersak and we became good friends,

spending many hours discussing our mutual

passion in Brussels and also at my home in

Venice, California.

A. A.: What are kifwebe masks to you and

why such an interest in them? What has this

long “specialization” taught you?

W. D.: First of all, I should say, I am not

a scholar. I’m an artist and an obsessive

collector of these striped masks of the Songye

and Luba peoples. Which is not to say I don’t

have my own hypotheses here and there,

but I will leave all of the anthropological

discussions to the scholars. For me, bifwebe