90

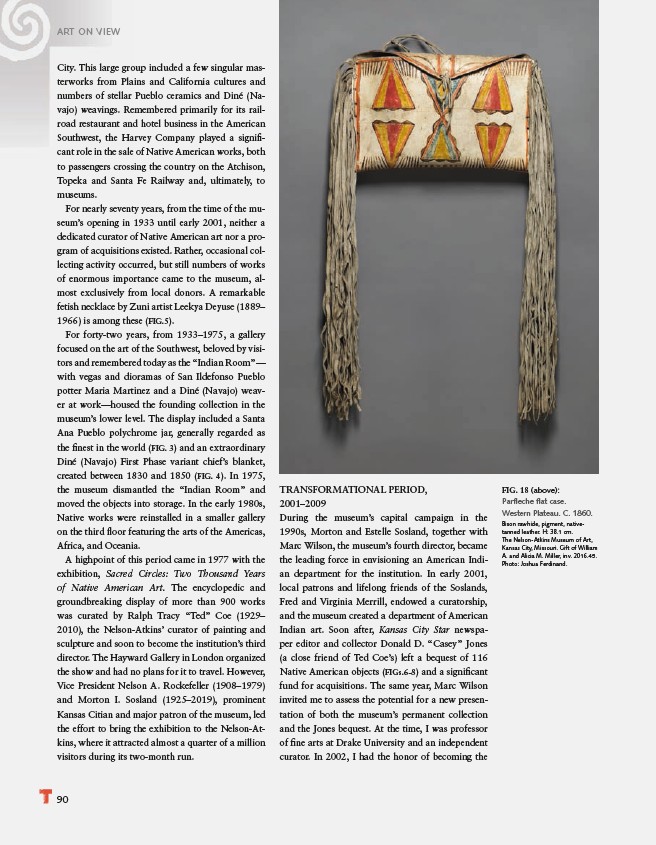

FIG. 18 (above):

Parfl eche fl at case.

Western Plateau. C. 1860.

Bison rawhide, pigment, nativetanned

leather. H: 38.1 cm.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art,

Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of William

A. and Alicia M. Miller, inv. 2016.45.

Photo: Joshua Ferdinand.

TRANSFORMATIONAL PERIOD,

2001–2009

During the museum’s capital campaign in the

1990s, Morton and Estelle Sosland, together with

Marc Wilson, the museum’s fourth director, became

the leading force in envisioning an American Indian

department for the institution. In early 2001,

local patrons and lifelong friends of the Soslands,

Fred and Virginia Merrill, endowed a curatorship,

and the museum created a department of American

Indian art. Soon after, Kansas City Star newspaper

editor and collector Donald D. “Casey” Jones

(a close friend of Ted Coe’s) left a bequest of 116

Native American objects (FIGs.6-8) and a signifi cant

fund for acquisitions. The same year, Marc Wilson

invited me to assess the potential for a new presentation

of both the museum’s permanent collection

and the Jones bequest. At the time, I was professor

of fi ne arts at Drake University and an independent

curator. In 2002, I had the honor of becoming the

ART ON VIEW

City. This large group included a few singular masterworks

from Plains and California cultures and

numbers of stellar Pueblo ceramics and Diné (Navajo)

weavings. Remembered primarily for its railroad

restaurant and hotel business in the American

Southwest, the Harvey Company played a signifi -

cant role in the sale of Native American works, both

to passengers crossing the country on the Atchison,

Topeka and Santa Fe Railway and, ultimately, to

museums.

For nearly seventy years, from the time of the museum’s

opening in 1933 until early 2001, neither a

dedicated curator of Native American art nor a program

of acquisitions existed. Rather, occasional collecting

activity occurred, but still numbers of works

of enormous importance came to the museum, almost

exclusively from local donors. A remarkable

fetish necklace by Zuni artist Leekya Deyuse (1889–

1966) is among these (FIG.5).

For forty-two years, from 1933–1975, a gallery

focused on the art of the Southwest, beloved by visitors

and remembered today as the “Indian Room”—

with vegas and dioramas of San Ildefonso Pueblo

potter Maria Martinez and a Diné (Navajo) weaver

at work—housed the founding collection in the

museum’s lower level. The display included a Santa

Ana Pueblo polychrome jar, generally regarded as

the fi nest in the world (FIG. 3) and an extraordinary

Diné (Navajo) First Phase variant chief’s blanket,

created between 1830 and 1850 (FIG. 4). In 1975,

the museum dismantled the “Indian Room” and

moved the objects into storage. In the early 1980s,

Native works were reinstalled in a smaller gallery

on the third fl oor featuring the arts of the Americas,

Africa, and Oceania.

A highpoint of this period came in 1977 with the

exhibition, Sacred Circles: Two Thousand Years

of Native American Art. The encyclopedic and

groundbreaking display of more than 900 works

was curated by Ralph Tracy “Ted” Coe (1929–

2010), the Nelson-Atkins’ curator of painting and

sculpture and soon to become the institution’s third

director. The Hayward Gallery in London organized

the show and had no plans for it to travel. However,

Vice President Nelson A. Rockefeller (1908–1979)

and Morton I. Sosland (1925–2019), prominent

Kansas Citian and major patron of the museum, led

the effort to bring the exhibition to the Nelson-Atkins,

where it attracted almost a quarter of a million

visitors during its two-month run.