Charles Ratton,

Louis Carré,

and the Landmark

Auctions of 1931

1931

94

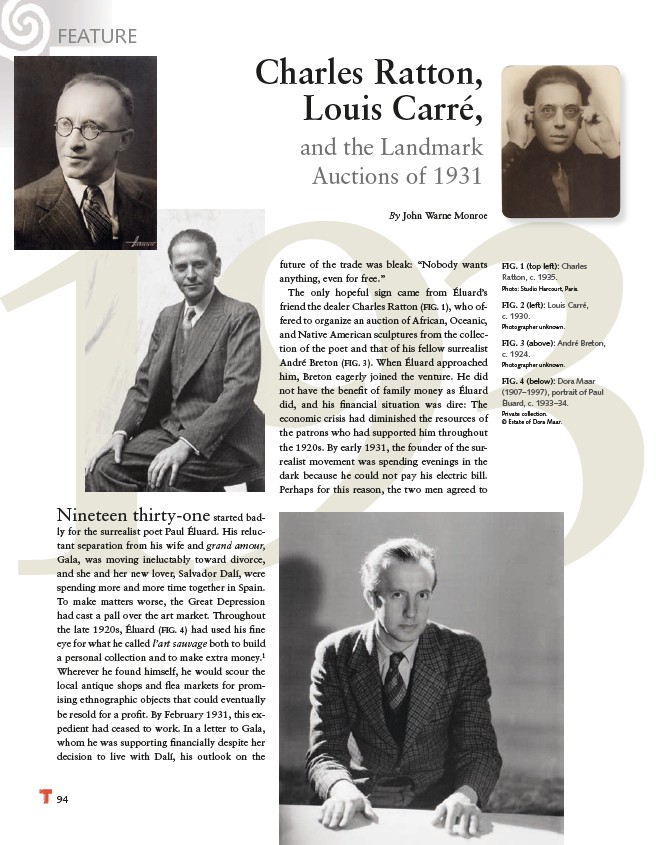

FIG. 1 (top left): Charles

Ratton, c. 1935.

Photo: Studio Harcourt, Paris.

FIG. 2 (left): Louis Carré,

c. 1930.

Photographer unknown.

FIG. 3 (above): André Breton,

c. 1924.

Photographer unknown.

FIG. 4 (below): Dora Maar

(1907–1997), portrait of Paul

Éluard, c. 1933–34.

Private collection.

© Estate of Dora Maar.

Nineteen thirty-one started badly

for the surrealist poet Paul Éluard. His reluctant

separation from his wife and grand amour,

Gala, was moving ineluctably toward divorce,

and she and her new lover, Salvador Dalí, were

spending more and more time together in Spain.

To make matters worse, the Great Depression

had cast a pall over the art market. Throughout

the late 1920s, Éluard (FIG. 4) had used his fi ne

eye for what he called l’art sauvage both to build

a personal collection and to make extra money.1

Wherever he found himself, he would scour the

local antique shops and fl ea markets for promising

ethnographic objects that could eventually

be resold for a profi t. By February 1931, this expedient

had ceased to work. In a letter to Gala,

whom he was supporting fi nancially despite her

decision to live with Dalí, his outlook on the

By John Warne Monroe

future of the trade was bleak: “Nobody wants

anything, even for free.”

The only hopeful sign came from Éluard’s

friend the dealer Charles Ratton (FIG. 1), who offered

to organize an auction of African, Oceanic,

and Native American sculptures from the collection

of the poet and that of his fellow surrealist

André Breton (FIG. 3). When Éluard approached

him, Breton eagerly joined the venture. He did

not have the benefi t of family money as Éluard

did, and his fi nancial situation was dire: The

economic crisis had diminished the resources of

the patrons who had supported him throughout

the 1920s. By early 1931, the founder of the surrealist

movement was spending evenings in the

dark because he could not pay his electric bill.

Perhaps for this reason, the two men agreed to

FEATURE