also act independently, organizing sales which

they can then present to an étude.

Ratton’s path to offi cial recognition as an expert—

a degree in art history followed by notable

success as an antique dealer—was typical, but his

interest in ethnographic art made him unique.

Where experts usually specialize in fi elds with

highly developed scholarly literature and long

market histories, in 1931 the fi eld of art primitif

was still new. As Philippe Dagen has pointed

out, there were no systematic published compilations

of African sculptural styles. That would

have to wait for Carl Kjersmeier’s groundbreaking

books, the fi rst of which appeared in 1935.14

There were no courses at the Ecole du Louvre

and the offerings of the recently founded Institut

d’Ethnologie were tailored more to social scien-

99

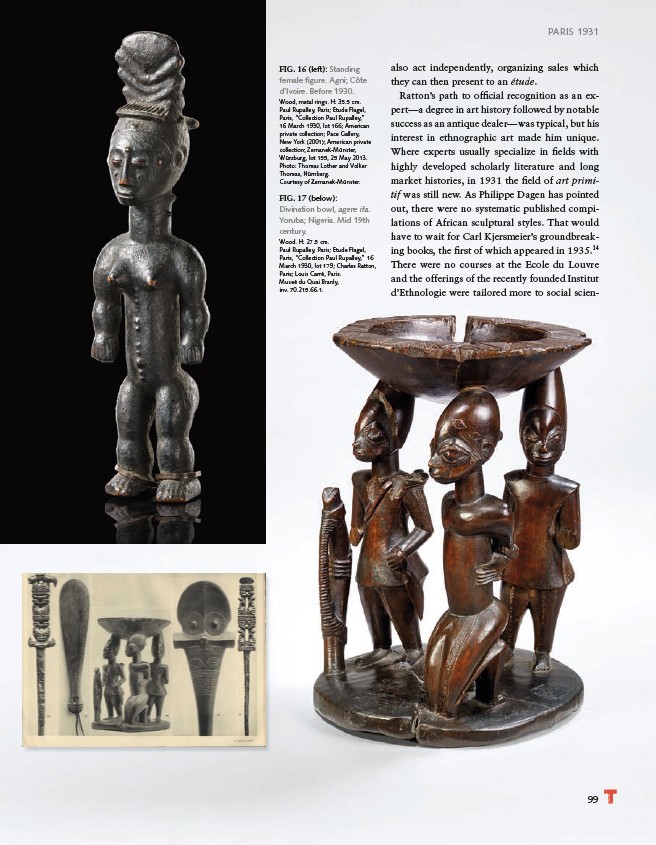

FIG. 16 (left): Standing

female fi gure. Agni; Côte

d’Ivoire. Before 1930.

Wood, metal rings. H: 35.5 cm.

Paul Rupalley, Paris; Étude Flagel,

Paris, “Collection Paul Rupalley,”

16 March 1930, lot 166; American

private collection; Pace Gallery,

New York (2001); American private

collection; Zemanek-Münster,

Würzburg, lot 155, 25 May 2013.

Photo: Thomas Lother and Volker

Thomas, Nürnberg.

Courtesy of Zemanek-Münster.

FIG. 17 (below):

Divination bowl, agere ifa.

Yoruba; Nigeria. Mid 19th

century.

Wood. H: 27.5 cm.

Paul Rupalley, Paris; Étude Flagel,

Paris, “Collection Paul Rupalley,” 16

March 1930, lot 179; Charles Ratton,

Paris; Louis Carré, Paris.

Museé du Quai Branly,

inv. 70.215.66.1.

PARIS 1931