FEATURE

and Northwest America,” in which “beautiful

pieces abound.”24 Unfortunately, however, Flagel

and Portier made a serious miscalculation in

presenting their collector to the public. A month

before the sale of Rupalley’s ethnographic art,

there had been an auction of his European and

Asian objects. The Asian pieces, as a reporter

for Paris-Soir noted, “did not differ much from

what one sees in many collections,” but the European

104

material was more memorable: It included

“the skeleton of a fetus, sold for 8 francs;

late eighteenth-century lorgnettes (35 francs);

three police billy-clubs, bagpipes, a ship’s compass,

pencil boxes, etc.” As the auction continued,

prospective bidders “succumbed to a gentle

hilarity”—and the reporter himself admitted

to chuckling at the thought of the man “who

spent every morning carefully running his feather

duster over the 149 objects in his collection of

European art.”25 When Rupalley’s ethnographic

art was sold a month later, the aftertaste of the

previous auction lingered, and the objects on offer

“did not achieve particularly high prices.”26

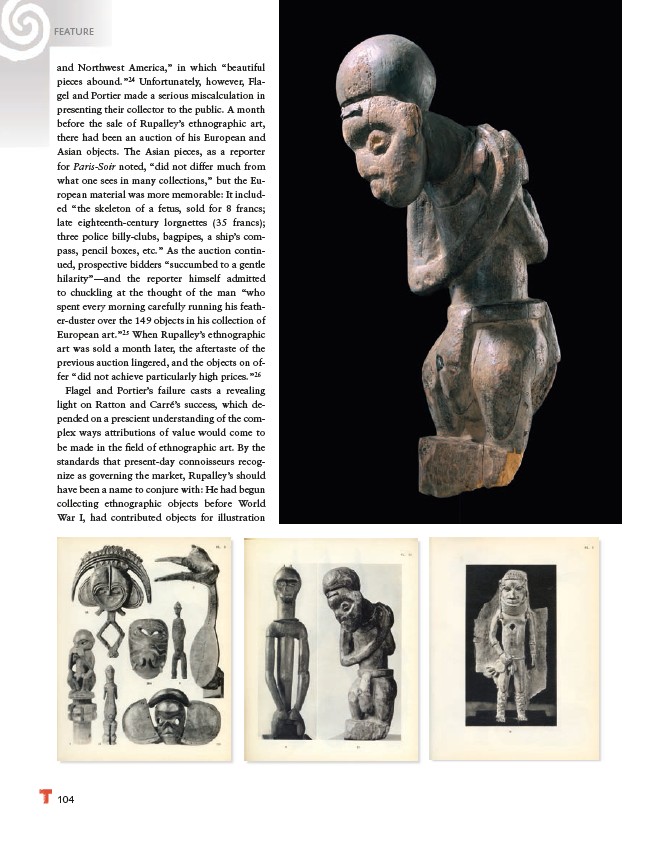

Flagel and Portier’s failure casts a revealing

light on Ratton and Carré’s success, which depended

on a prescient understanding of the complex

ways attributions of value would come to

be made in the fi eld of ethnographic art. By the

standards that present-day connoisseurs recognize

as governing the market, Rupalley’s should

have been a name to conjure with: He had begun

collecting ethnographic objects before World

War I, had contributed objects for illustration