PORTFOLIO

100

world.” In both cases, Ratton argued, such telltale

signs as color, “hesitating engraving,” “fi letouch,”

and stylistic inconsistency could reveal

the forger’s hand.16

Since in France the offi cial status of expert entailed

heavy legal and fi nancial responsibilities,

pioneering a new area in this way was a considerable

risk. Rather than taking the gamble for

the 1931 sales alone, Ratton chose to do it in

partnership with Louis Carré, a fellow antique

dealer who was then somewhat more established

in the business. His father had been in the

trade as well, and by the time Ratton befriended

him around 1930, the thirty-two-year-old Carré

had already written a well-known guide to hallmarks

on gold and silver. In a draft of a letter

from 1930, when their business relationship was

just beginning, Ratton expressed admiration for

Carré’s “impressive book on silverware” and

described him as “a newcomer to primitive arts

who is also a chap with a high culture” and

therefore prepared to do the research necessary

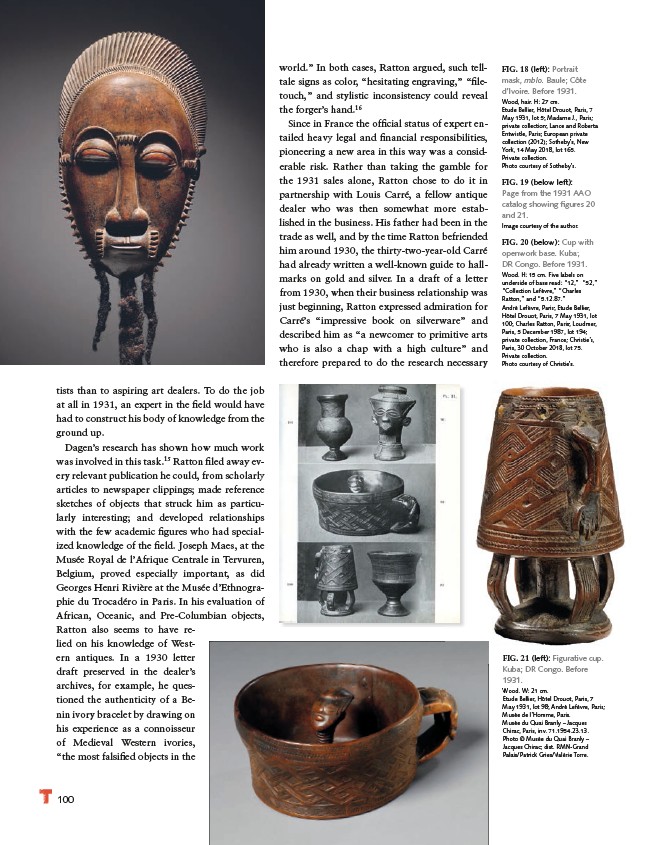

FIG. 18 (left): Portrait

mask, mblo. Baule; Côte

d’Ivoire. Before 1931.

Wood, hair. H: 27 cm.

Étude Bellier, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 7

May 1931, lot 5; Madame J., Paris;

private collection; Lance and Roberta

Entwistle, Paris; European private

collection (2012); Sotheby’s, New

York, 14 May 2018, lot 165.

Private collection.

Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

FIG. 19 (below left):

Page from the 1931 AAO

catalog showing fi gures 20

and 21.

Image courtesy of the author.

FIG. 20 (below): Cup with

openwork base. Kuba;

DR Congo. Before 1931.

Wood. H: 15 cm. Five labels on

underside of base read: “12,” “52,”

“Collection Lefèvre,” “Charles

Ratton,” and “5.12.87.”

André Lefèvre, Paris; Étude Bellier,

Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 7 May 1931, lot

100; Charles Ratton, Paris; Loudmer,

Paris, 5 December 1987, lot 194;

private collection, France; Christie’s,

Paris, 30 October 2018, lot 75.

Private collection.

Photo courtesy of Christie’s.

FIG. 21 (left): Figurative cup.

Kuba; DR Congo. Before

1931.

Wood. W: 21 cm.

Étude Bellier, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 7

May 1931, lot 98; André Lefèvre, Paris;

Musée de l’Homme, Paris.

Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques

Chirac, Paris, inv. 71.1954.23.13.

Photo © Musée du Quai Branly –

Jacques Chirac; dist. RMN-Grand

Palais/Patrick Gries/Valérie Torre.

tists than to aspiring art dealers. To do the job

at all in 1931, an expert in the fi eld would have

had to construct his body of knowledge from the

ground up.

Dagen’s research has shown how much work

was involved in this task.15 Ratton fi led away every

relevant publication he could, from scholarly

articles to newspaper clippings; made reference

sketches of objects that struck him as particularly

interesting; and developed relationships

with the few academic fi gures who had specialized

knowledge of the fi eld. Joseph Maes, at the

Musée Royal de l’Afrique Centrale in Tervuren,

Belgium, proved especially important, as did

Georges Henri Rivière at the Musée d’Ethnographie

du Trocadéro in Paris. In his evaluation of

African, Oceanic, and Pre-Columbian objects,

Ratton also seems to have relied

on his knowledge of Western

antiques. In a 1930 letter

draft preserved in the dealer’s

archives, for example, he questioned

the authenticity of a Benin

ivory bracelet by drawing on

his experience as a connoisseur

of Medieval Western ivories,

“the most falsifi ed objects in the