PARIS 1931

105

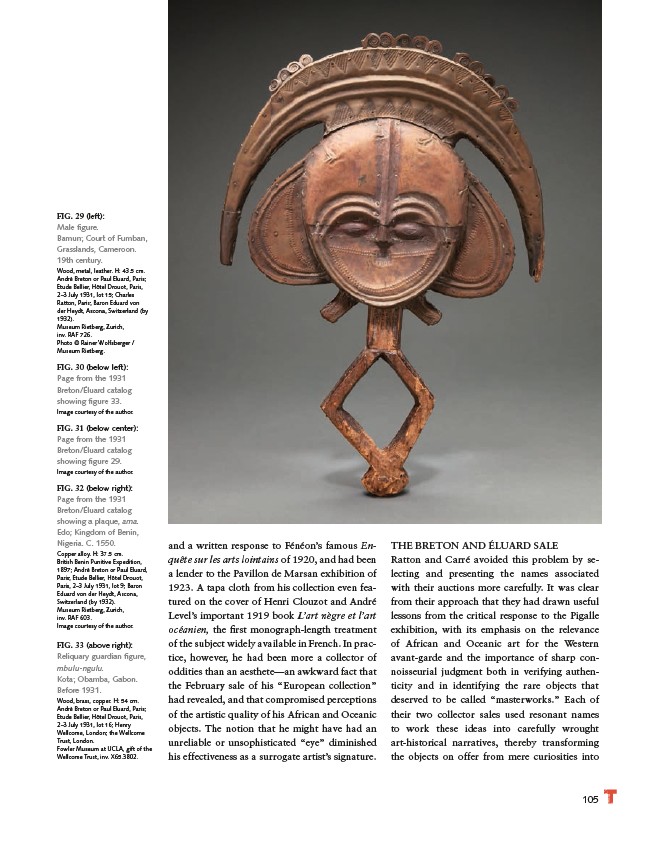

FIG. 29 (left):

Male figure.

Bamun; Court of Fumban,

Grasslands, Cameroon.

19th century.

Wood, metal, leather. H: 43.5 cm.

André Breton or Paul Éluard, Paris;

Étude Bellier, Hôtel Drouot, Paris,

2–3 July 1931, lot 15; Charles

Ratton, Paris; Baron Eduard von

der Heydt, Ascona, Switzerland (by

1932).

Museum Rietberg, Zurich,

inv. RAF 726.

Photo © Rainer Wolfsberger /

Museum Rietberg.

FIG. 30 (below left):

Page from the 1931

Breton/Éluard catalog

showing figure 33.

Image courtesy of the author.

FIG. 31 (below center):

Page from the 1931

Breton/Éluard catalog

showing figure 29.

Image courtesy of the author.

FIG. 32 (below right):

Page from the 1931

Breton/Éluard catalog

showing a plaque, ama.

Edo; Kingdom of Benin,

Nigeria. C. 1550.

Copper alloy. H: 37.5 cm.

British Benin Punitive Expedition,

1897; André Breton or Paul Eluard,

Paris; Étude Bellier, Hôtel Drouot,

Paris, 2–3 July 1931, lot 9; Baron

Eduard von der Heydt, Ascona,

Switzerland (by 1932).

Museum Rietberg, Zurich,

inv. RAF 603.

Image courtesy of the author.

FIG. 33 (above right):

Reliquary guardian figure,

mbulu-ngulu.

Kota; Obamba, Gabon.

Before 1931.

Wood, brass, copper. H: 54 cm.

André Breton or Paul Eluard, Paris;

Étude Bellier, Hôtel Drouot, Paris,

2–3 July 1931, lot 16; Henry

Wellcome, London; the Wellcome

Trust, London.

Fowler Museum at UCLA, gift of the

Wellcome Trust, inv. X65.3802.

and a written response to Fénéon’s famous Enquête

sur les arts lointains of 1920, and had been

a lender to the Pavillon de Marsan exhibition of

1923. A tapa cloth from his collection even featured

on the cover of Henri Clouzot and André

Level’s important 1919 book L’art nègre et l’art

océanien, the first monograph-length treatment

of the subject widely available in French. In practice,

however, he had been more a collector of

oddities than an aesthete—an awkward fact that

the February sale of his “European collection”

had revealed, and that compromised perceptions

of the artistic quality of his African and Oceanic

objects. The notion that he might have had an

unreliable or unsophisticated “eye” diminished

his effectiveness as a surrogate artist’s signature.

THE BRETON AND ÉLUARD SALE

Ratton and Carré avoided this problem by selecting

and presenting the names associated

with their auctions more carefully. It was clear

from their approach that they had drawn useful

lessons from the critical response to the Pigalle

exhibition, with its emphasis on the relevance

of African and Oceanic art for the Western

avant-garde and the importance of sharp connoisseurial

judgment both in verifying authenticity

and in identifying the rare objects that

deserved to be called “masterworks.” Each of

their two collector sales used resonant names

to work these ideas into carefully wrought

art-historical narratives, thereby transforming

the objects on offer from mere curiosities into