ART ON VIEW

86

and the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery

of Art in the lobby and west wing. They

were formally combined as the Nelson-Atkins

Museum of Art in 1983.

The lead architect, Thomas Wright, has

been extensively quoted as saying, “We are building

the museum on classic principles because they have

been proved by the centuries. A distinctly American

principle appropriate for such a building may

be developed, but, so far, everything of that kind

is experimental. One doesn’t experiment with two

and a half million dollars.”

That may well have been the last non-experimental

moment at the Nelson-Atkins. From its outset,

it has shown remarkable vision in its collecting,

display, and interpretation. Planning for the Bloch

Building extension, which added 165,000 square

feet, began in 1993 and the building opened in

2007 to critical acclaim. Designed by Steven Holl,

it is sometimes described as a high-rise building on

its side. Its gallery spaces move above and below

ground as it undulates down the hillside to the

southeast of the original building. In striking contrast

to Wright’s perspective, New York Times architecture

critic Nicolai Ouroussoff described it as

“a building that doesn’t challenge the past so much

as suggest an alternate world view that is in constant

shift.” And “It’s an approach that should be

studied by anyone who sets out to design a museum

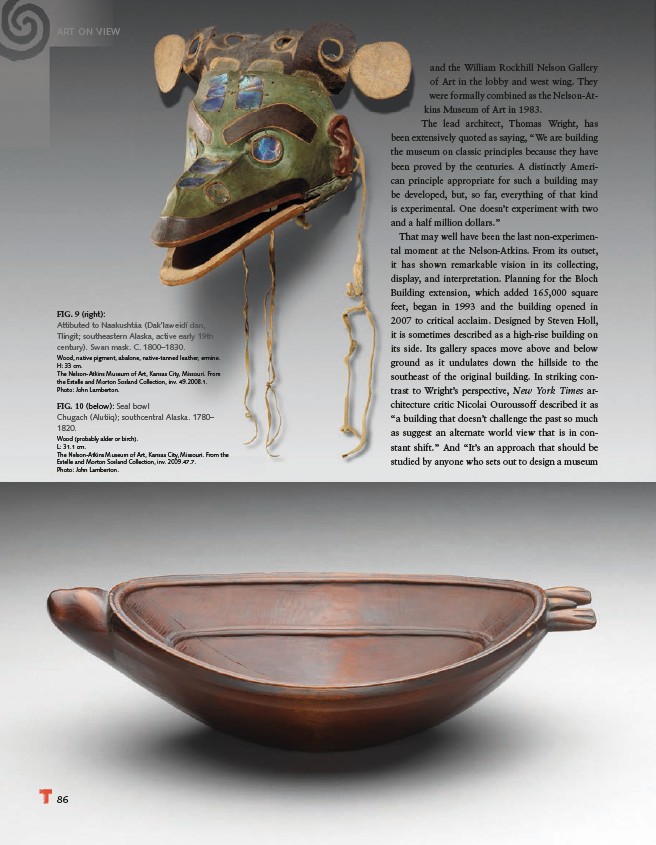

FIG. 9 (right):

Attibuted to Naakushtáa (Dak’laweidí clan,

Tlingit; southeastern Alaska, active early 19th

century). Swan mask. C. 1800–1830.

Wood, native pigment, abalone, native-tanned leather, ermine.

H: 33 cm.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. From

the Estelle and Morton Sosland Collection, inv. 49.2008.1.

Photo: John Lamberton.

FIG. 10 (below): SeaI bowI

Chugach (Alutiiq); southcentral Alaska. 1780–

1820.

Wood (probably alder or birch).

L: 31.1 cm.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. From the

Estelle and Morton Sosland Collection, inv. 2009.47.7.

Photo: John Lamberton.