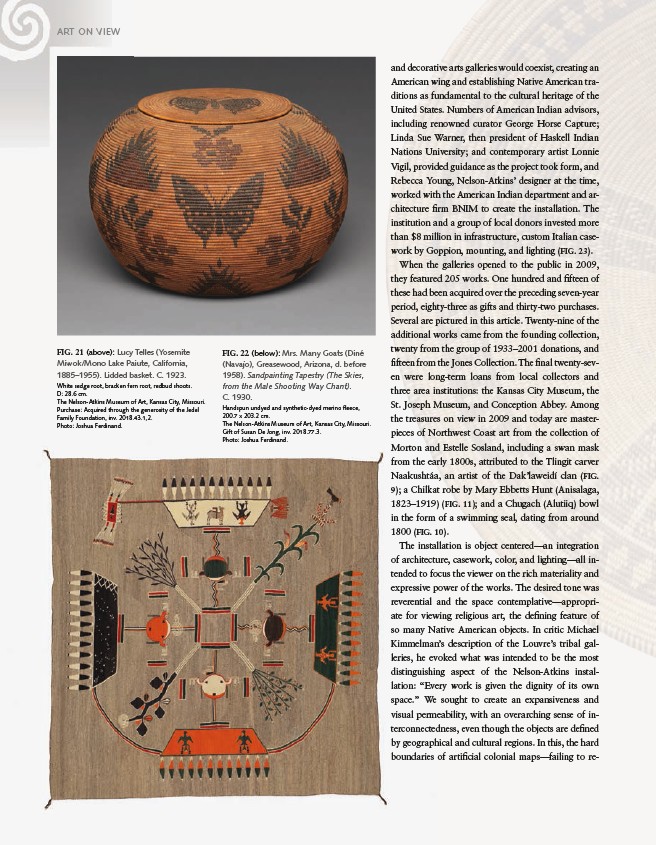

FIG. 21 (above): Lucy Telles (Yosemite

Miwok/Mono Lake Paiute, California,

1885–1955). Lidded basket. C. 1923.

White sedge root, bracken fern root, redbud shoots.

D: 28.6 cm.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri.

Purchase: Acquired through the generosity of the Jedel

Family Foundation, inv. 2018.43.1,2.

Photo: Joshua Ferdinand.

116

FIG. 22 (below): Mrs. Many Goats (Diné

(Navajo), Greasewood, Arizona, d. before

1958). Sandpainting Tapestry (The Skies,

from the MaIe Shooting Way Chant).

C. 1930.

Handspun undyed and synthetic-dyed merino fl eece,

200.7 x 203.2 cm.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri.

Gift of Susan De Jong, inv. 2018.77.3.

Photo: Joshua Ferdinand.

ART ON VIEW

and decorative arts galleries would coexist, creating an

American wing and establishing Native American traditions

as fundamental to the cultural heritage of the

United States. Numbers of American Indian advisors,

including renowned curator George Horse Capture;

Linda Sue Warner, then president of Haskell Indian

Nations University; and contemporary artist Lonnie

Vigil, provided guidance as the project took form, and

Rebecca Young, Nelson-Atkins’ designer at the time,

worked with the American Indian department and architecture

fi rm BNIM to create the installation. The

institution and a group of local donors invested more

than $8 million in infrastructure, custom Italian casework

by Goppion, mounting, and lighting (FIG. 23).

When the galleries opened to the public in 2009,

they featured 205 works. One hundred and fi fteen of

these had been acquired over the preceding seven-year

period, eighty-three as gifts and thirty-two purchases.

Several are pictured in this article. Twenty-nine of the

additional works came from the founding collection,

twenty from the group of 1933–2001 donations, and

fi fteen from the Jones Collection. The fi nal twenty-seven

were long-term loans from local collectors and

three area institutions: the Kansas City Museum, the

St. Joseph Museum, and Conception Abbey. Among

the treasures on view in 2009 and today are masterpieces

of Northwest Coast art from the collection of

Morton and Estelle Sosland, including a swan mask

from the early 1800s, attributed to the Tlingit carver

Naakushtáa, an artist of the Dak’laweidí clan (FIG.

9); a Chilkat robe by Mary Ebbetts Hunt (Anisalaga,

1823–1919) (FIG. 11); and a Chugach (Alutiiq) bowl

in the form of a swimming seal, dating from around

1800 (FIG. 10).

The installation is object centered—an integration

of architecture, casework, color, and lighting—all intended

to focus the viewer on the rich materiality and

expressive power of the works. The desired tone was

reverential and the space contemplative—appropriate

for viewing religious art, the defi ning feature of

so many Native American objects. In critic Michael

Kimmelman’s description of the Louvre’s tribal galleries,

he evoked what was intended to be the most

distinguishing aspect of the Nelson-Atkins installation:

“Every work is given the dignity of its own

space.” We sought to create an expansiveness and

visual permeability, with an overarching sense of interconnectedness,

even though the objects are defi ned

by geographical and cultural regions. In this, the hard

boundaries of artifi cial colonial maps—failing to re-