121

FIG. 41 (left):

Male fi gure.

Admiralty Islands, Papua

New Guinea. Before 1931.

Wood, vegetal fi ber, pigment.

H: 154.9 cm.

André Breton or Paul Éluard, Paris;

Étude Bellier, Hôtel Drouot, Paris,

2–3 July 1931, lot 122; Henry

Wellcome, London; the Wellcome

Trust, London.

Fowler Museum at UCLA, gift of the

Wellcome Trust, inv. X65.4990.

Photo: Don Cole.

FIG. 42 (right): Page from

the 1931 Breton/Éluard

catalog showing fi gures 41

and 43.

Image courtesy of the author.

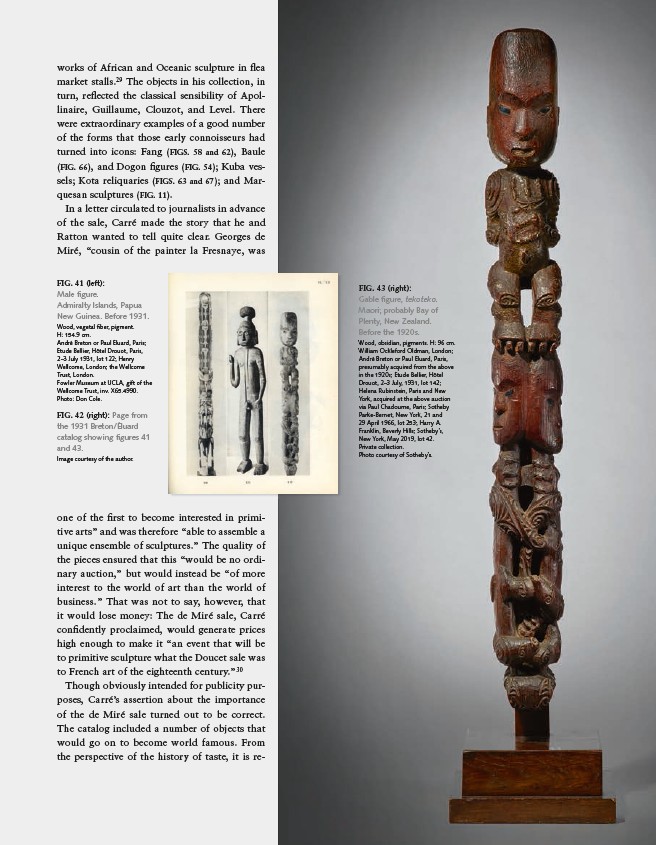

FIG. 43 (right):

Gable fi gure, tekoteko.

Maori; probably Bay of

Plenty, New Zealand.

Before the 1920s.

Wood, obsidian, pigments. H: 96 cm.

William Ockleford Oldman, London;

André Breton or Paul Éluard, Paris,

presumably acquired from the above

in the 1920s; Étude Bellier, Hôtel

Drouot, 2–3 July, 1931, lot 142;

Helena Rubinstein, Paris and New

York, acquired at the above auction

via Paul Chadourne, Paris; Sotheby

Parke-Bernet, New York, 21 and

29 April 1966, lot 253; Harry A.

Franklin, Beverly Hills; Sotheby’s,

New York, May 2019, lot 42.

Private collection.

Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

works of African and Oceanic sculpture in fl ea

market stalls.29 The objects in his collection, in

turn, refl ected the classical sensibility of Apollinaire,

Guillaume, Clouzot, and Level. There

were extraordinary examples of a good number

of the forms that those early connoisseurs had

turned into icons: Fang (FIGS. 58 and 62), Baule

(FIG. 66), and Dogon fi gures (FIG. 54); Kuba vessels;

Kota reliquaries (FIGS. 63 and 67); and Marquesan

sculptures (FIG. 11).

In a letter circulated to journalists in advance

of the sale, Carré made the story that he and

Ratton wanted to tell quite clear. Georges de

Miré, “cousin of the painter la Fresnaye, was

one of the fi rst to become interested in primitive

arts” and was therefore “able to assemble a

unique ensemble of sculptures.” The quality of

the pieces ensured that this “would be no ordinary

auction,” but would instead be “of more

interest to the world of art than the world of

business.” That was not to say, however, that

it would lose money: The de Miré sale, Carré

confi dently proclaimed, would generate prices

high enough to make it “an event that will be

to primitive sculpture what the Doucet sale was

to French art of the eighteenth century.”30

Though obviously intended for publicity purposes,

Carré’s assertion about the importance

of the de Miré sale turned out to be correct.

The catalog included a number of objects that

would go on to become world famous. From

the perspective of the history of taste, it is re-