130

PORTFOLIO

F. L. KENETT

A Forgotten Legend

By Kevin Conru

“Unquestionably the greatest photographer

of sculpting in the world who himself

became a sculptor,” wrote art critic T. G. Rosenthal

in The Listener in 1966.1 Such was the reputation

of Frederick Leslie Kenett at the moment he

turned his back on sculpture photography in the

mid 1960s and became a prolifi c sculptor himself.

And for the nearly fi fty years that followed, Kenett

remained a Kensington London recluse, devoting

himself to making abstract works in the manner

of the modernist taste prevalent at the time.

Born as Frederick Leslie Cohen in Berlin in

1924, the son of a Jewish doctor, Kenett escaped

to England in 1939. He changed his name to Kenett

(later known professionally as F. L. Kenett),

and, after a brief period of aimless occupations,

he joined the U.S. Military Intelligence Corps

during the war, where he developed an interest

in photography. Later, he furthered his studies of

photography at the Guildford School of Art, and

in 1951 he won the school’s prestigious Summer

Prize for photographs of sculptures by Michelangelo.

A year later, Kenett got his fi rst major

commission. Various government bodies planned

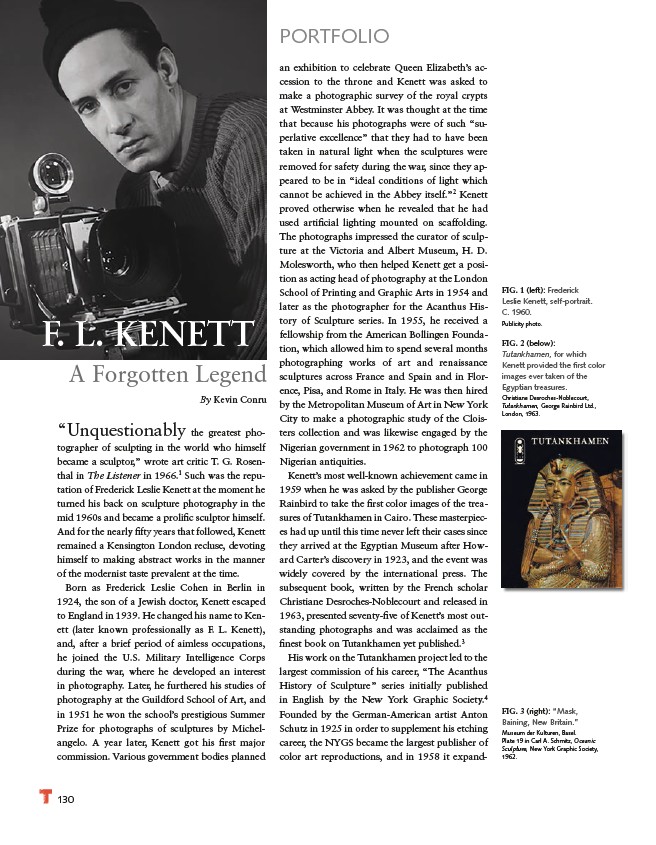

FIG. 1 (left): Frederick

Leslie Kenett, self-portrait.

C. 1960.

Publicity photo.

FIG. 2 (below):

Tutankhamen, for which

Kenett provided the fi rst color

images ever taken of the

Egyptian treasures.

Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt,

Tutankhamen, George Rainbird Ltd.,

London, 1963.

FIG. 3 (right): “Mask,

Baining, New Britain.”

Museum der Kulturen, Basel.

Plate 19 in Carl A. Schmitz, Oceanic

Sculpture, New York Graphic Society,

1962.

an exhibition to celebrate Queen Elizabeth’s accession

to the throne and Kenett was asked to

make a photographic survey of the royal crypts

at Westminster Abbey. It was thought at the time

that because his photographs were of such “superlative

excellence” that they had to have been

taken in natural light when the sculptures were

removed for safety during the war, since they appeared

to be in “ideal conditions of light which

cannot be achieved in the Abbey itself.”2 Kenett

proved otherwise when he revealed that he had

used artifi cial lighting mounted on scaffolding.

The photographs impressed the curator of sculpture

at the Victoria and Albert Museum, H. D.

Molesworth, who then helped Kenett get a position

as acting head of photography at the London

School of Printing and Graphic Arts in 1954 and

later as the photographer for the Acanthus History

of Sculpture series. In 1955, he received a

fellowship from the American Bollingen Foundation,

which allowed him to spend several months

photographing works of art and renaissance

sculptures across France and Spain and in Florence,

Pisa, and Rome in Italy. He was then hired

by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

City to make a photographic study of the Cloisters

collection and was likewise engaged by the

Nigerian government in 1962 to photograph 100

Nigerian antiquities.

Kenett’s most well-known achievement came in

1959 when he was asked by the publisher George

Rainbird to take the fi rst color images of the treasures

of Tutankhamen in Cairo. These masterpieces

had up until this time never left their cases since

they arrived at the Egyptian Museum after Howard

Carter’s discovery in 1923, and the event was

widely covered by the international press. The

subsequent book, written by the French scholar

Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt and released in

1963, presented seventy-fi ve of Kenett’s most outstanding

photographs and was acclaimed as the

fi nest book on Tutankhamen yet published.3

His work on the Tutankhamen project led to the

largest commission of his career, “The Acanthus

History of Sculpture” series initially published

in English by the New York Graphic Society.4

Founded by the German-American artist Anton

Schutz in 1925 in order to supplement his etching

career, the NYGS became the largest publisher of

color art reproductions, and in 1958 it expand-