101

new intensive research in the Congo will again

one day be possible in order to bring fresh data

to light remains to be seen, but I hope that my

new book will at least incite others to pick up

the threads and fi ll in the blanks.

Among the contributions of Luluwa: Central

African Art between Heaven and Earth is

its selection of some 160 works from public

and private collections around the world. Together

these illustrate the arresting diversity of

sculpture that has been designated as Luluwa.

However, despite the exhaustive ambition of

this project, the number of fi gures, masks, and

decorative art objects illustrated in the book,

though not insignifi cant, merely represents a

choice of what has been preserved and, at best,

a sampling of what likely was produced but did

not survive. Aside from my emphasis on sculpture

in wood, which is the medium most readily

available in museums and collections in Europe

and the United States, I have also elected to focus

on what art scholars, collectors, and dealers

have come to recognize as the “classical style” of

Luluwa fi gurative art. However, the distinction

between classical and non-classical quickly fades

in the borderland areas of Luluwaland, where

the boundaries between the arts of the Luluwa

and those of neighboring groups are dynamic

and blurred. With regard to masks, it must be

acknowledged that some of the best-known ex-

FIG. 3 (left):

Dyamba dance in Mukenge.

From Hermann von Wissmann et al.,

Im Innern Afrikas: Die Erforschung

des Kassaï während der Jahre 1883,

1884 und 1885 (3rd ed.), Berlin:

Globus, 1891, facing p. 184.

Propagated by chief Kalamba-

Mukenge in the late nineteenth

century, a new religion centered on

the smoking of cannabis, or dyamba,

was originally meant to promote

peace, joy, and eternal life.

FIG. 4 (facing page, right):

Power object.

Possibly Luluwa, Democratic

Republic of the Congo.

Animal horn, warthog tusk, metal,

earth. H: 20 cm.

Ex Fodor, Belgium; Joëlle Fiess,

Belgium.

Felix Collection, Belgium.

Photo: Courtesy Congo Basin Art

History Research Center, Brussels.

Natural containers such as animal

horns, monkey skulls, and snail shells

were among the most commonly

found forms of personal and portable

medicine-charged power objects,

or manga.

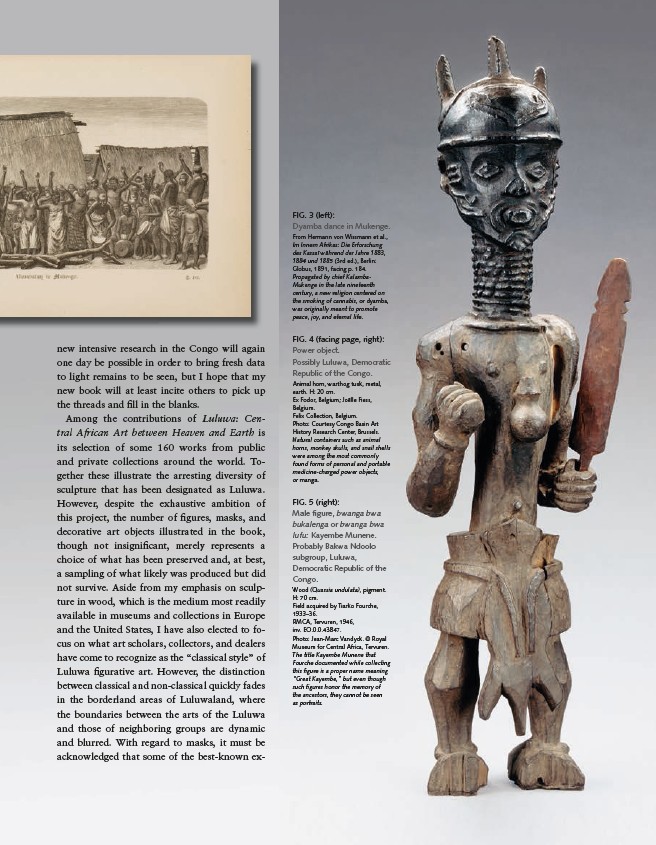

FIG. 5 (right):

Male fi gure, bwanga bwa

bukalenga or bwanga bwa

lufu: Kayembe Munene.

Probably Bakwa Ndoolo

subgroup, Luluwa,

Democratic Republic of the

Congo.

Wood (Quassia undulata), pigment.

H: 70 cm.

Field acquired by Tiarko Fourche,

1933–36.

RMCA, Tervuren, 1946,

inv. EO.0.0.43847.

Photo: Jean-Marc Vandyck. © Royal

Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren.

The title Kayembe Munene that

Fourche documented while collecting

this fi gure is a proper name meaning

“Great Kayembe,” but even though

such fi gures honor the memory of

the ancestors, they cannot be seen

as portraits.