109

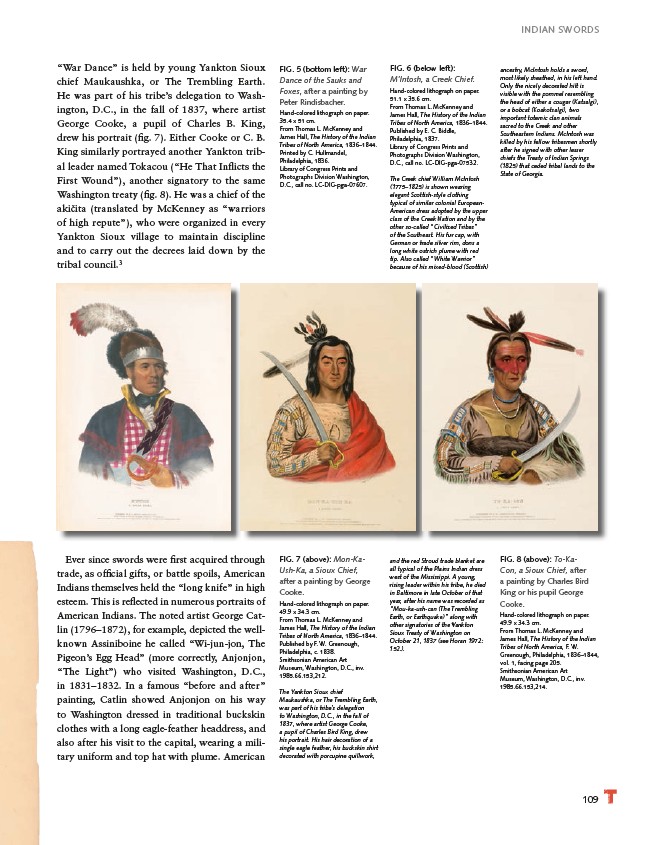

FIG. 5 (bottom left): War

Dance of the Sauks and

Foxes, after a painting by

Peter Rindisbacher.

Hand-colored lithograph on paper.

35.4 x 51 cm.

From Thomas L. McKenney and

James Hall, The History of the Indian

Tribes of North America, 1836–1844.

Printed by C. Hullmandel,

Philadelphia, 1836.

Library of Congress Prints and

Photographs Division Washington,

D.C., call no. LC-DIG-pga-07607.

FIG. 6 (below left):

M’Intosh, a Creek Chief.

Hand-colored lithograph on paper.

51.1 x 35.6 cm.

From Thomas L. McKenney and

James Hall, The History of the Indian

Tribes of North America, 1836–1844.

Published by E. C. Biddle,

Philadelphia, 1837.

Library of Congress Prints and

Photographs Division Washington,

D.C., call no. LC-DIG-pga-07532.

The Creek chief William McIntosh

(1775–1825) is shown wearing

elegant Scottish-style clothing

typical of similar colonial European-

American dress adopted by the upper

class of the Creek Nation and by the

other so-called “Civilized Tribes”

of the Southeast. His fur cap, with

German or trade silver rim, dons a

long white ostrich plume with red

tip. Also called “White Warrior”

because of his mixed-blood (Scottish)

ancestry, McIntosh holds a sword,

most likely sheathed, in his left hand.

Only the nicely decorated hilt is

visible with the pommel resembling

the head of either a cougar (Katsalgi),

or a bobcat (Koakotsalgi), two

important totemic clan animals

sacred to the Creek and other

Southeastern Indians. McIntosh was

killed by his fellow tribesmen shortly

after he signed with other lesser

chiefs the Treaty of Indian Springs

(1825) that ceded tribal lands to the

State of Georgia.

FIG. 7 (above): Mon-Ka-

Ush-Ka, a Sioux Chief,

after a painting by George

Cooke.

Hand-colored lithograph on paper.

49.9 x 34.3 cm.

From Thomas L. McKenney and

James Hall, The History of the Indian

Tribes of North America, 1836–1844.

Published by F. W. Greenough,

Philadelphia, c. 1838.

Smithsonian American Art

Museum, Washington, D.C., inv.

1985.66.153,212.

The Yankton Sioux chief

Maukaushka, or The Trembling Earth,

was part of his tribe’s delegation

to Washington, D.C., in the fall of

1837, where artist George Cooke,

a pupil of Charles Bird King, drew

his portrait. His hair decoration of a

single eagle feather, his buckskin shirt

decorated with porcupine quillwork,

and the red Stroud trade blanket are

all typical of the Plains Indian dress

west of the Mississippi. A young,

rising leader within his tribe, he died

in Baltimore in late October of that

year, after his name was recorded as

“Mou-ka-ush-can (The Trembling

Earth, or Earthquake)” along with

other signatories of the Yankton

Sioux Treaty of Washington on

October 21, 1837 (see Horan 1972:

152.).

FIG. 8 (above): To-Ka-

Con, a Sioux Chief, after

a painting by Charles Bird

King or his pupil George

Cooke.

Hand-colored lithograph on paper.

49.9 x 34.3 cm.

From Thomas L. McKenney and

James Hall, The History of the Indian

Tribes of North America, F. W.

Greenough, Philadelphia, 1836–1844,

vol. 1, facing page 205.

Smithsonian American Art

Museum, Washington, D.C., inv.

1985.66.153,214.

“War Dance” is held by young Yankton Sioux

chief Maukaushka, or The Trembling Earth.

He was part of his tribe’s delegation to Washington,

D.C., in the fall of 1837, where artist

George Cooke, a pupil of Charles B. King,

drew his portrait (fi g. 7). Either Cooke or C. B.

King similarly portrayed another Yankton tribal

leader named Tokacou (“He That Infl icts the

First Wound”), another signatory to the same

Washington treaty (fi g. 8). He was a chief of the

akicita (translated by McKenney as “warriors

of high repute”), who were organized in every

Yankton Sioux village to maintain discipline

and to carry out the decrees laid down by the

tribal council.3

Ever since swords were fi rst acquired through

trade, as offi cial gifts, or battle spoils, American

Indians themselves held the “long knife” in high

esteem. This is refl ected in numerous portraits of

American Indians. The noted artist George Catlin

(1796–1872), for example, depicted the wellknown

Assiniboine he called “Wi-jun-jon, The

Pigeon’s Egg Head” (more correctly, Anjonjon,

“The Light”) who visited Washington, D.C.,

in 1831–1832. In a famous “before and after”

painting, Catlin showed Anjonjon on his way

to Washington dressed in traditional buckskin

clothes with a long eagle-feather headdress, and

also after his visit to the capital, wearing a military

uniform and top hat with plume. American

INDIAN SWORDS